Getting started in film cheap, easy, says local filmmaker

February 6, 2011 by Amanda Punshon · 5 Comments

Quentin Tarantino taught himself the history of film. Sir Ridley Scott worked on roughly 2,700 commercials before he made it big with Alien. Robert Rodriguez sold his body to science to fund his filmmaking.

These guys are incredibly passionate about film. It’s easy for them to make movies because they have lots of money. But they didn’t always, and if you want to make your own films, you don’t need to be rich either.

Rob Hunt is a local independent filmmaker. Like Tarantino, he didn’t go to film school. He says he would have if he’d had the money, but film programs are really expensive.

“I think that the problem with a film program is that you go and you spend all this money, and you don’t walk away with any equipment. So you really have to be aware of that. If you’re going to be in a film program, you have to be there 110%. You’ve got to be using the equipment, you’ve got to be making friends and contacts,” Hunt says.

And, of course, there’s no guarantee that you’ll get a job once you graduate.

Hunt, who has a degree in computer science from the University of Victoria, has filmed two feature films and purchased all of his own equipment in approximately the same time as a film program would take.

He’s currently directing Standard Action, the Dungeons & Dragons-themed webseries he co-created with girlfriend Joanna Gaskell.

Hunt isn’t afraid of a little competition. In fact, he welcomes it.

“I wanna see cool stuff, and I don’t like what the big studios are doing,” he says. “You’ll see ideas come from independent film that studios are not willing to take a risk on.”

EQUIPMENT

If you want to make your own film, Hunt says you only need a few simple things.

The first is a digital single-lens reflex camera that shoots HD video. Hunt shoots Standard Action on a Canon T2i, which costs around $800. The 7D is also a good option, Hunt says, but it’s a lot more expensive.

Buying a cheaper camera means less of a financial loss if the camera is broken or confiscated. It also means you can buy a second camera, which saves time because it allows you to shoot a scene from two angles at the same time.

Hunt quotes Stu Maschwitz, the man behind filmmaking blog Prolost, as recommending the T2i over the 7D because it has recently been hacked, which has unlocked (for free) a lot of features that would ordinarily come on cameras that cost thousands of dollars more. The hack is pretty recent, so he advises waiting a few months before using it on your camera to make sure it’s stable.

If you buy your camera in a kit it will come with a couple of lenses, but Hunt advises upgrading them. He says a fast 50mm lens, which costs around $100, will work well in low-light situations. It’s also a good idea to get a wide-angle lens, he says, and a “reasonable” tripod.

DSLR cameras shoot beautiful video but the audio quality isn’t very good, so you’ll have to buy an external recording device of some kind. Hunt uses the Zoom H4n (around $350) on Standard Action, but he says he’s seen sound guys using even simpler devices with good results.

Hunt says that, in addition to the recorder, you’ll need a microphone. “You need a basic boom mic and boom pole. A boom pole is like 50 bucks, and boom mic or shotgun microphone, those are like 200 dollars.”

And since you’ll be recording your audio and video separately, you’ll need a slate (also known as a clapboard) which is basically a piece of plastic or wood with two pieces that click when they’re brought together. It makes adding the separate audio track to the video easy during the editing process – you just line both up at the click.

“That’s kind of old school and it’s come back again as a real requirement,” Hunt says.

If you’d like to dabble a bit in lighting, Hunt recommends starting with a good bounce (also known as a reflector) to hold under actors’ faces for close-ups. “It just makes the face a little bit lighter, and more professionally-lit looking,” Hunt says.

A basic lighting kit can come in handy, too. They have just three small 300-watt lights, but DSLR cameras are so good in low-light that that’s all you need. Hunt just bought one for around $300. He’ll be using it during the production of Standard Action episode four.

There’s also a nifty little camera-mounted LED light that’s great for making actors’ faces pop when shooting close-ups. According to Hunt, it’s handy for filming in forests because it maintains the dark, spooky atmosphere, but lights the actors very well. And in daylight situations, it provides more control over the quality of the light. Hunt says he found his for around $40 on eBay.

PEOPLE

“If you want to make film, you need a friend who is gullible enough to come out, hold the boom mic, and learn how to use whatever thing you’ve got to record sound,” Hunt says.

“You need a guy who knows how to make sure that he knows that he’s recording and not just listening to the sound, cuz there is that big difference. And to be able to not shake the boom mic around, cuz that’s important.”

Another handy person to have around is a set decorator. Hunt says that the addition of a set decorator has made Standard Action look that much more professional. And if you hire someone who can also do other things, like design costumes or operate your second camera, it will make your life that much easier and save you a lot of time.

WEBSITES

Hunt found his set decorator on Craigslist. “I’ve seen some great miracles happen from the people I’ve pulled off of Craigslist. I’ve had some incredibly talented and enthusiastic people,” he says.

“Don’t be afraid to try to find other people, just be ready to have a little bit of friction or find people who don’t actually help.”

Hunt advises posting the “gigs” section, because you have a better chance of finding people who share your passion for filmmaking and will volunteer their time to help you out.

If you need to fundraise, Hunt says IndieGoGo is the way to go. Creators set up pages on the fan-funding site and then anyone, anywhere can donate as much money as they like to the project. Hunt says it allows filmmakers to approach people they normally wouldn’t for funding, and thanks to IndieGoGo, he is now looking at being able to afford a premiere for his movie, The Director’s Project.

“That website alone has changed the whole game in the last year, and i really look forward to how that’s going to expand. I think that’s just going to get a lot better for us,” Hunt says.

And for those interested in special effects, Hunt says Video Copilot is a great site to visit. It’s run by Andrew Kramer, who created the title sequences for Fringe and the Star Trek movie. The site offers free tutorials in Adobe After Effects, which allows filmmakers to “make someone’s leg or head blow off” without any danger.

BOOKS

Hunt speaks very highly of the DV Rebel’s Guide: An All-Digital Approach to Making Killer Action Movies on the Cheap. He says “it’s like 80 bucks, but it’s like the Bible, or like a textbook. It’s not necessarily a storybook, but it’s everything you could need.”

He also highly recommends Robert Rodriguez’s memoir Rebel Without a Crew. “It’s the kind of book you read if you’re feeling down and you don’t want to make film any more. You read it, and then you want to do it again. ‘Cause, like, he sold his body to science to do it, and lived in an institution…it’s pretty epic.”

Hunt reads a lot. “Buy books on amazon and read them,” he says. “That’s how you really become a good filmmaker.”

OTHER MATERIALS

DVD commentaries are also a great source of information. Again, Hunt recommends Robert Rodriguez’s movies, because his commentaries and extras are geared toward filmmakers.

And the Lord of the Rings, with its 12 hours of commentary, “is such a huge wealth of stuff.” In addition to directors and actors, there are commentaries by the set designers, costume-makers and art designers. Hunt says that the ideas in commentaries are a good way to learn about what does and doesn’t show up on-camera so that you can pull off professional-looking special effects and costumes without having to spend a lot of money.

Hunt also recommends the DVD boxed set of The Middleman. The show, which ran for a single season in 2008, was based on a comic book about a girl recruited by a guy who fixes weird problems for a living to be his replacement.

COURSES

Kwantlen doesn’t offer any filmmaking classes, but Hunt says there are still some useful courses in the calendar.

The first, and most basic, is an introductory English course. Hunt says he once read a screenwriting book that advised writers to use the same essay-writing techniques he learned at university.

“Writing scripts for me…is very similar to writing a ten-page essay,” he says. “I’ll make notecards and I’ll lay them out on the ground, and it’s exactly the same as how i used to write long essays.”

Hunt doesn’t personally have a problem generating story ideas or writing fiction, but he says that if it’s a skill you need to work on, creative writing classes are a must. Kwantlen offers several that might interest filmmakers, including Introduction to Creative Writing I and II (CRWR 1100 and 1110), Drama, Fiction and Poetry I and II (CRWR 2300 and 2310) and Screenwriting I and II (CRWR 3120 and 3220.)

Jason Lieblang, who teaches German Culture through Film (CUST 3300,) thinks that his course would be beneficial for aspiring filmmakers too.

“You definitely don’t learn the practical skills necessary to make films in a class like mine, that is, editing and how to work a camera and those types of things,” Leiblang says. “You do learn about the history of cinema, about the great directors, about great sort of shifts in filmmaking that were crucial and important and affected the way that films were made after that.”

He also teaches students how to analyze films as texts, looking narrative and form so that students can understand film in a “a deeper, more profound way.”

On top of that, he teaches his students how to “communicate clearly, effectively and persuasively” by writing short argumentative essays.

And rather that writing a final paper, Leiblang says that students can do other kinds of projects, including making a film, if they can prove that they will satisfy the requirements of the assignment.

Kwantlen’s course calendar promises that Introduction to Film Studies (ARTH 1130) will teach students about the “history and development of world cinema” and about “film as a visual language and art-making practice,” and says that students “will learn methods for exploring aesthetic function and for considering the social, political, and technological contexts” of movies. This, like Lieblang’s German Culture Through Film class, will teach you some basic film terms and give you a good grounding in the interpretation of film.

If you’re interested in understanding film and having a lot of control over the way your films are interpreted, Eryne Donahue’s Introduction to Visual Culture (FINA 1167) course may be for you. Donahue says that her class will help students understand films from a variety of perspectives.

“[Filmmakers] could sort of get a sense of how that stuff is put together and then how it’s read by the public,” she says. “They could from there get a sense of what’s already out there and how they could maybe contribute to it.”

Donahue also teaches Photography I (FINA 1170) which is the closest thing Kwantlen offers to a filmmaking class. She says it would be very beneficial for anyone who wants to make movies because a lot of the the language and principles involved are the same.

“It gives a pretty good understanding of how film works. They’re based on the same sort of principles, right, technically. And if they’re taking the course it also sort of slows them down because we’re dealing with film-based cameras instead of digital to start. They really have to kind of focus and put a lot of emphasis on the choices they make and that would set them up really well for storyboarding and planning for film,” she says.

She has some advice for students who want to get into film, too.

“The student should be prepared to do a lot of work,” Donahue says. “There’s no sort of standard path, really, with film or any of the arts, so you have to have a strong vision in mind to know really where you want to go with it.”

Links:

For more of the Chronicle’s coverage of independent arts in Vancouver, click here.

To watch Standard Action click here

Click here for Rob Hunt’s website.

Stu Maschwitz’s blog is here.

Video Copilot, which offers free special effects tutorials for filmmakers, is here.

Check Kwantlen’s course calendar for useful courses.

Amazon, Craigslist and IndieGoGo are useful sites for filmmakers.

Tom Segura: The man behind the laughter

February 4, 2011 by Meagan Gill · Leave a Comment

It’s all laughs at the Comedy Mix on Saturday night as headliner Tom Segura takes the stage.

Patrick Maliha, the MC, prepares audience members for Segura by describing him as awesome and describing how he blew the roof off the venue on the night before.

He does it again. From talking about people with no teeth, to comparing living in LA to living in prison, Segura has the audience roaring with laughter. After the show, he stands outside the venue selling his album Thrilled, which features nearly an hour of his comedy. Members of the audience stopped to talk to Segura, including one man who claims he hadn’t laughed that hard in a very long time.

Segura is a comedian from LA, whose favourite comedians have included Bill Cosby, Eddie Murphy, Chris Rock, George Carlin, Dave Attell and Dave Chapelle.

“I feel like I’m always being inspired by different people,” Segura says.

Segura was born in Cincinnati, but moved around a lot growing up. He started thinking about a career in comedy when he was 18, and became set on the idea when he was 21. He decided to move once more, this time to LA, to pursue a career in comedy. He started taking classes at an improv school where a couple of his fellow students, who were stand-up comedians, took him out to a couple of different clubs to show him what it was all about. Three weeks later he started trying it out himself.

“I’ve always liked doing it; making people laugh and I really liked performing,” says Segura.

He describes his first year doing comedy as awkward. “It was like a discovery thing, like just figuring out how to get a feel for it. I didn’t know what I was doing so it was about figuring out the little stuff, like how to walk on stage and how to take the mic out,” he says. Most importantly, “it was about learning how to fail, miserably.”

A lot of embarrassing things can happen during stand-up comedy, especially at the beginning of a career. “There’s everything from flubbing what you say to forgetting a joke, but I think the most embarrassing thing is getting really upset,” Segura says.

He recalls losing his cool on a couple of occasions when someone in the audience yelled something at him. He now believes the best way to deal with hecklers is to not let them get under your skin: in order to come out on top, you have to be funny back at them.

“If you lose your cool, which I’ve done, it’s really embarrassing. It throws everything off. You don’t want to do that but sometimes you feel undermined because somebody just mocked you,” says Segura.

Segura says ideas for jokes just come to him. It’s not something he really plans for. “I’ll just be having a conversation with someone, and then start thinking, ‘Hey, that could be a good joke’,” he says.

He also comes up with jokes by writing about something he thinks about a lot. “If there’s something you’re always thinking about, that’s usually a trigger that you should write about it and a joke will just come to you,” he says.

For Segura, what makes a good comedic performance is someone who has a solid point of view.

“It’s always better as an audience member to watch someone who is not just funny, but interesting. It really heightens the performance,” he says. Segura also believes that a good performance is a combination of material, personality and energy.

His advice to beginner comedians is to “quit now, don’t do it,” he says.

Jokes aside, Segura says “you have to write a lot and get on stage as much as you can. It sounds obvious, but there really are no shortcuts. You need to perform a lot, you should be on stage every night, like at least six nights a week.”

If Segura could go back, he says he would have started doing comedy earlier. “It took me awhile to gain that momentum, because at first, it’s really intimidating to try to be an entertainer basically,” he says.

Some of the highlights of his career include having a special that recently aired on the Comedy Network, doing festivals in Montreal, Las Vegas and Vancouver, and getting the opportunity to open for Russell Peters in front of 16,500 people.

“I’ve been pretty lucky that I’ve been able to do some pretty cool things. I don’t feel like there’s just one highlight, I feel like it’s been a lot of different things,” he says.

Segura believes there’s a strong future for stand-up comedy.

“I think it’s exciting right now. There’s like a resurgence going on. You go to these clubs and it’s packed, the show is sold out. That’s a really good thing to see and it’s inspiring to see that people still want to go to live shows. And there’s so many young comics to watch. I think there’s a really bright future for stand-up comedy,” he says.

To learn more about Tom Segura and his tour dates, visit his website.

Guerrilla filmmaking is a risky but rewarding endeavor

February 4, 2011 by Brian Russell · 2 Comments

Edwin Perez and Joanna Gaskell party it up in between takes on the set of the web series “Standard Action”, which is usually filmed on location without permits. (photo courtesy of Standard Action website)

Guerrilla filmmakers aren’t a bunch of James Bonds or 1950s beatniks, but what they do has them constantly looking at the dangling boulder of consequence hanging over their heads.

Being a guerrilla filmmaker often means filming illegally in public areas, where permits are required, but also means making a movie free of Hollywood standards.

Guerilla filmmakers are working with significantly low budgets, on purpose. The movement believes strongly in the artistic effort.

Rob Hunt, director of the fantasy-themed web series Standard Action, has one thought about the guerrilla work he has done in the past.

“I would love to redo all the things I’ve ever made with the people who walk their dogs through the scene. You’re having an epic moment, and then dude and his wife walk by with their tiny dog. And it’s like, ‘Hey, just go through’,” said Hunt.

And while the frequent possibility of people walking into frame is always keeping the guerrilla filmmaker vigilant, the much greater threat of facing a hefty fine for filming without a permit, or even being arrested, looms.

Hunt recalls a story he heard about a filmmaking experience gone awry.

“I know other people who have had issues…[a guy] had [fake] guns and they were filming in a house, so it was totally legitimate, and then one of the actors wandered out in the alley…and was posing with it, and then people called the cops and next thing you know, dude’s on the ground with a real gun pointed at his head,” Hunt said.

Working on a tight budget already, having to cough up any amount of money to something other than their masterpiece certainly isn’t helpful. But what about the equipment? That stuff must not come cheap, right?

It’s true, it can be costly to invest in the right equipment, but Hunt says that if you have a decent DSLR camera, such as a Canon Rebel T2i, and good sound equipment, including a boom mic, you’re all set to start shooting.

You’ll also need a cast. Hunt recommends Craigslist as a good source of finding actors and crew members, but warns that it can also be a sour experience.

“I’ve seen some great miracles happen from the people I’ve pulled off of Craigslist…just be ready to have a little bit of friction or find people who don’t actually help,” said Hunt.

Guerrilla filmmaking allows those without the money to film big-budget productions live out their passion for making movies and being creative. Hunt is an advocate for it for one other reason.

“You’ll see ideas come from independent film that studios are not willing to take a risk on,” he said.

Some mainstream directors got their start working guerrilla style, including Black Swan director Darren Aronofsky and Malcolm X director Spike Lee.

Desturbia: Hoping to become established through a web series

January 31, 2011 by Sarah Casimong · Leave a Comment

Allen Kumar, independent director and screenwriter, is currently shooting his web series Desturbia, set to go online in December. (Photo by Sarah Casimong)

Aspiring filmmakers don’t need a TV network or theatrical distributor anymore: they have the web.

That’s what Allen Kumar, a rookie director and screenwriter, is using for his first project, Desturbia. Desturbia is an independent murder mystery web series, currently shooting in different parts of Metro Vancouver.

“First what I was going to do was take it to a network. I wanted to establish myself and wanted to work as a PA [production assistant] or something, get in there [for] a few years, then pitch it to a network,” said Kumar.

He changed his mind after deciding that he wanted the freedom to make decisions on his own.

“In a web series, I can do it [all] myself,” said Kumar. “I won’t have a big budget but I can show that I can do it. And if I have a show that has people involved and people who are watching it, I can take it to a network and get a web series picked up, which I want to do after two seasons.

“If you look at it now, shows on network TV, they rely on a lot of ratings,” said Kumar. “Because you have a lower budget and you have more control of it, your web series can’t get canceled. Especially not at the beginning. So if you use a web series to get an audience, it shows the network that the show draws in people.”

Three years ago, Kumar started writing a screenplay out of boredom, basing the story on a crime that happened in his life. What started out as a 10-minute short became 30 minutes. Kumar considered making a film, but that idea didn’t last long.

“You can’t tell this story in a movie,” said Kumar. “You have to show the elements and have conflict and all the things building up to make this actually look real. Because if you make this into a movie, it will become some cheesy horror film, which I’m not trying to do. I’m trying to show [the story] and why these people did this.”

Kumar decided that a web series would be a perfect way to tell the story and develop the characters over a longer period of time.

“The internet is the best way right now. Not many people watch TV as much because everything is online with Youtube and MegaVideo. Studios are actually making web series now.” said Kumar.

An example, he said, is the TV series Ghost Whisperer which was canceled and then turned into a web series.

Although he is funding Desturbia on his own, he says sites such as IndieGoGo are a way to get funding. Other ways are through fundraising events or reaching out to businesses.

“It [can be] a lower budget, so you won’t be spending too much. Some web series, you don’t even need a major studio. You can shoot it in your bedroom.”

Although Kumar had to drop an expensive car chase scene from the pilot episode, because of the budget, he is still happy to see his vision played out.

“The best part would be the fact that when I write [the script] I don’t know if it’s really good but when I actually see it, when the actors play it out, I’m like ‘I must be good,’” said Kumar. “I know [the actors] add their own personalities and stuff, but the fact that it’s basically what the scene is actually about and it actually works and you [can] see it, it seems real, like you’re watching something on television.”

Desturbia is set to premiere in December or January 2012. For more information, visit Cyrus Entertainment’s website.

Filming in Vancouver: $650 a day for a park, $95 an hour for a cop

January 30, 2011 by Meagan Gill · Leave a Comment

The cost of filming is one of the biggest issues facing independent filmmakers in Vancouver.

The City of Vancouver’s Vancouver Film Office was set up to deal with on-location filming while ensuring the safety of the public and protecting the rights of local neighbourhoods. It handles all productions in Vancouver, ranging from independent films and commercials to feature films and television series. And while the office helps production companies get the authorization to film on public property and on city streets, the price can be high, especially for independent filmmakers.

According to the city’s website, it costs about $650 a day to film at any major parks or beaches, while the permit for filming in neighbourhood parks is about $590 a day.

Any filming that affects the normal use of public property requires a Film Activity Permit. Each day of filming or different location requires at least one Film Activity Permit, which is approximately $150.

A street-use permit is approximately $150, but the amount of street space being used for filming will determine how many permits are required to shoot the scene.

The use of a Vancouver police officer in filming is $95 an hour and a sergeant is $119 an hour. Using a fire engine in filming costs $110 per hour and firefighters are $82 per hour each. Vancouver Fire and Rescue Services Training Classroom is available for $400 per day and the Training Academy is available at the rate of $1,500 per day.

Lori Clarkson, film liaison at the Vancouver Film Office, says that the cost of film permits is the same for independent filmmakers as it is for professional filmmakers.

“From our point of view, if a production crew is asking us to do some work, it doesn’t matter whose asking us to do the work. We have to be paid for the work we do, so it doesn’t matter if it’s a huge feature or a small independent feature,” said Clarkson.

There are some ways the city can cut back on some of the costs for independent filmmakers.

“One of the things that we can do is consider lessening the cost of a street-use permit, but it depends on what it is they need,” Clarkson said. “Typically, our fees are set by city council, so they are pretty much set in stone. But in some situations, we might be able to knock a little bit more off the cost of a permit.”

To find out more about the cost of film permits in the city of Vancouver, visit the Vancouver Film Office website.

Social media changes funding, distribution for indie filmmakers

January 30, 2011 by Jocelyn Gollner · 1 Comment

Social media is changing the way that we do almost everything and that now includes how independent filmmakers are funding and distributing their films.

“Everything is changing so quickly that 10 years from now, we won’t even recognize what it is right now,” said Ryan Catherwood, an independent filmmaker from Vancouver.

IndieGoGo is one site that filmmakers are using to help get funding for their films.

Besides the obvious social media forms, such as Facebook and Twitter, there are also specialty sites such as IndieGoGo that filmmakers are using for their films. IndieGoGo defines itself as an international funding platform.

Catherwood has recently starting using IndieGoGo and said that it’s a different way to raise funds for a film.

You “basically just put a pitch up online and then cross your fingers that people want to invest in it and become a part of it,” he said. Anyone can create an account, and attempt to raise funds for almost anything.

This money can make a huge difference to independent filmmakers.

“I work at a rental shop and, like a lot of my friends, we’re all filmmakers and we want to spend our time and our energy and our passion in film, but we have to get supplementary jobs to afford that,” Catherwood said.

Funding a film isn’t the only problem; distributing that film is also sometimes an obstacle.

“Distribution is continually becoming a problem, besides just putting it up for free online,” Catherwood said. “There are not a lot of options for filmmakers these days. It’s kind of like the elephant in the room that no one wants to talk about right now, but I keep trying to bring it up and just say like we have to find a way to make money from our films.”

As much as social media can help filmmakers distribute their films, it also poses its own set of problems.

“YouTube came along and it’s kind of the Coca-Cola of Internet broadcasting. It’s hard to get an edge on them,” Catherwood said.

Amid all the changes, Catherwood doesn’t know what the future holds.

“I don’t know where the independents are going to end up,” he said. “Until the independents, like one of our own, creates something to distribute indie films on a larger scale, nothing is going to change. That’s kind of how I see it.”

Mint Records: Surviving as an independent record label

January 23, 2011 by Sarah Casimong · Leave a Comment

The main goal is survival.

Mint Records is entering its 20th year and co-founder Bill Baker admits that changes in the music industry are a threat to independent music labels.

“As flippant as that sounds, [survival] is the number one goal and it always has been,” said Baker. “It’s a challenge and right now it’s just about this adaptation and seeing what we can do. A lot of people in the business have changed entirely. Record labels basically don’t put out records anymore, rather they do artist management and merchandising and publishing and things like that. [They're] focusing on other [ways] of working with bands and still have the potential to generate income.”

Changes in the music industry have forced Mint Records, like other labels, to revamp the traditional way of putting out music. One of the label’s suppliers, which has manufactured its CDs since 1994, is taking its last breath this year.

“We focus a lot more on putting out vinyl now,” said Baker. “We’ve been forced to cut back on the kind of investments we can make on projects. [In the past], we would’ve probably put out a record knowing that it was barely gonna break even, if that. But it was something that we felt passionate about doing. Now we may either not do that, or we may release it digitally only through iTunes, so we’re not actually incurring any manufacturing costs. It’s changed the way that we do things, for sure.”

In the beginning

Mint Records came to life in 1991 when Baker and his co-founder Randy Iwata came up with the idea of starting a record label after they left CiTR, UBC’s student-run radio station.

The early ’90s saw the growth of the grunge scene in Seattle, which had a huge influence on Vancouver’s music scene. Baker describes it as a vibrant time.

“There were a lot of new venues and up-and-coming new bands and people starting out. The whole punk thing had, at that time, gone by the wayside. We were getting new kinds of music and people were starting to explore. We certainly had no lack of material when it came time to find a band to work with,” said Baker.

At that time, Canada’s music industry was mostly based in Toronto, with branches of a few major labels in Vancouver. But despite being present, according to Baker, they failed to engage the local music scene.

“We recognized a bit of a niche, I suppose,” said Baker. “We weren’t the only people to do that at the time either.”

Baker and Iwata noticed the success of local independent label Nettwerk, but still saw a number of unsigned bands with potential.

“Here we got all these bands playing, people coming to see them and nobody’s really putting out their records. To be on Nettwerk, you had to be, at that point, reasonably well established. There’s a huge gap here with all these bands that we like, where are they gonna go? The majors won’t put them out and they’re not likely to be on Nettwerk,” Baker said.

“The goal was to just document what was going on in the music community in Vancouver at the time. There weren’t very many outlets for that. We were thinking there’s so much happening here, this sort of thriving community and unless you’re here, nobody will know about it. Our intention was to publicize it in the short term and document it for prosperity.”

Mint managed to achieve commerical success with artists such as The New Pornographers, Neko Case and The Organ. But Baker names the experience of working with Cub, one of its first bands back in 1992, as their greatest achievement.

“When Cub came out, that was us just learning and we didn’t know what we were doing,” said Baker. “If there were 10 things we needed to learn to run a record label, we probably learned nine of them.”

Cub went on to sell thousands of records across Canada, Japan, Australia and the U.S.

“In terms of a non-quantifiable success, I think that was our greatest success because no one really knew who we were. We were virtually unknown by the time we put out the Cub record,” he said.

“The first record was just a guy who recorded in his basement, didn’t know what he was doing. I think people initially considered their music to be juvenile and very poorly played. Their music provided a refreshing counterpoint to what was going on elsewhere and it really caught on with people.

“To be able to take something that basically came from virtual unknowns all across the board and make it into something where we were selling hundreds of records a week just in Vancouver and doing interviews on the CBC… That was when we really went from nothing to something. I look back on that with tremendous fondness.”

Obstacles

“Like any record label that has survived that long, through all the changes that have taken place in the music industry, [Mint Records] had moments of success and moments where they’ve encountered some resistance and they’ve come out of it intact. They still exist,” said Kaitlin Fontana, author of Fresh at Twenty: The Oral History of Mint Records.

While bands breaking up is always a setback for a label, Mint also had to deal with Cargo Records, one of its largest Canadian distributors, going bankrupt in the late ’90s.

“In an agonizingly long process. It took six months of us trying to get the money they owed us and eventually we didn’t get anything,” said Baker. “They took a substantial amount of money of ours down with them when they went bankrupt and we were unable to pay a lot of our artists the royalties that we owed them for some time. One of the artists on the label decided that they didn’t feel like that was fair and so they had to leave.”

Baker added that those things happen in most businesses.

“Those are very frustrating things to have to get over and in many respects they were difficult lessons to learn [but] they were valuable. I don’t think we lost hope, obviously we kept going but there were trials.”

The current trial the label is facing is digital downloads.

“Those are the kind of obstacles that, no matter how plucky and optimistic you can be, there aren’t really that many ways to overcome it unless you change what you do substantially,” said Baker. He remains appreciative of Mint’s customers, crediting them for Mint’s survival.

“We’ve been lucky so far because I think for the large part, the people who are interested in the music we put out are typically more in the mindset of a collector or someone who is part of a community,” said Baker.

“I think when people are primarily focused on things like Top 40 music, they don’t necessarily have some personal investment in what’s on the radio all the time. There’s perhaps less of a stigma about downloading that one song for free than there is if it’s your friend’s band and you know that they’re working three jobs to be able to play in a band and you like them and you want to help them out. I think that’s why, until recently, we suffered a lot less in terms of a decline in CD sales because of all of this.”

The label has also put more focus on a new approach to earning money: licensing songs for film and television.

“It’s not an exaggeration to say that you could have one music use in a television or advertising situation that could probably pay more than the record could ever make in its history. For every one of those, there are hundreds that don’t get anything but it’s something that’s worth pursuing because there’s money there and there’s people that want to spend it.”

Another battle that independent music labels face is the number of people who see no use for a label, taking advantage of the internet to put out their music via MySpace or YouTube.

“Agruably anybody with an internet connection and Garage Band could put their music out for free,” said Baker. “But if everybody’s doing that, it sounds like a very democratic, wonderful type of situation but it also increases the general background noise. I don’t think people like being told what to like but I think people appreciate having guidance when there’s a million things to choose from. I think it’s meaningful to someone to be able to say ‘I like most of the records that I bought that are on Mint. Now they’re putting out another one, I’ll probably like it.’”

Fontana acknowledged the importance of Mint Records and the role it has played in Vancouver’s music scene.

“I wanted to write the book to point out that there has been this wonderful, underground scene and this wonderful pop scene in Vancouver that Mint Records has basically been chronicling for the last 20 years,” said Fontana. “If we ignore that, if we ignore the contribution that this label has made to the city, we’re ignoring a big part of our own culture and I don’t think that that’s a wise thing for any community to do.”

Baker hopes that Mint will continue putting out music that documents the scene in Vancouver, as it has done for the past 20 years.

“I think that there’s still a value to a record label,” said Baker. “I think as long as we could continue to find ways to put out music without just going bankrupt from doing it, that’s something that we’re always gonna do.”

What is Indie?

January 17, 2011 by Jocelyn Gollner · Leave a Comment

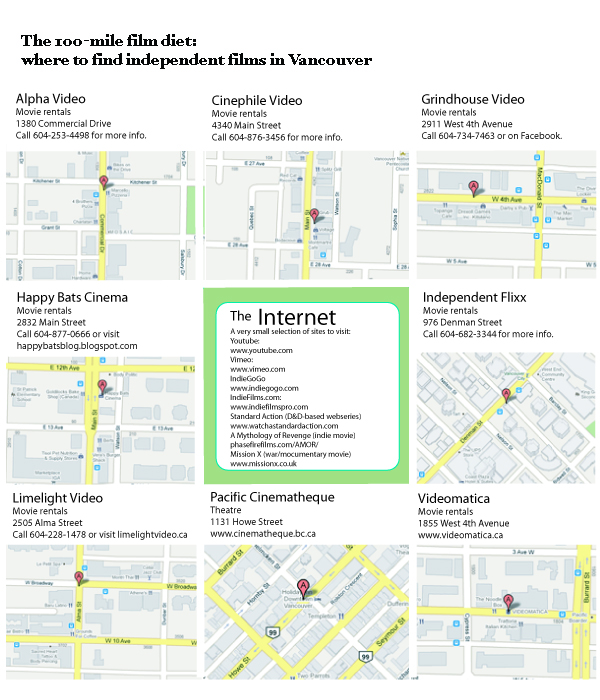

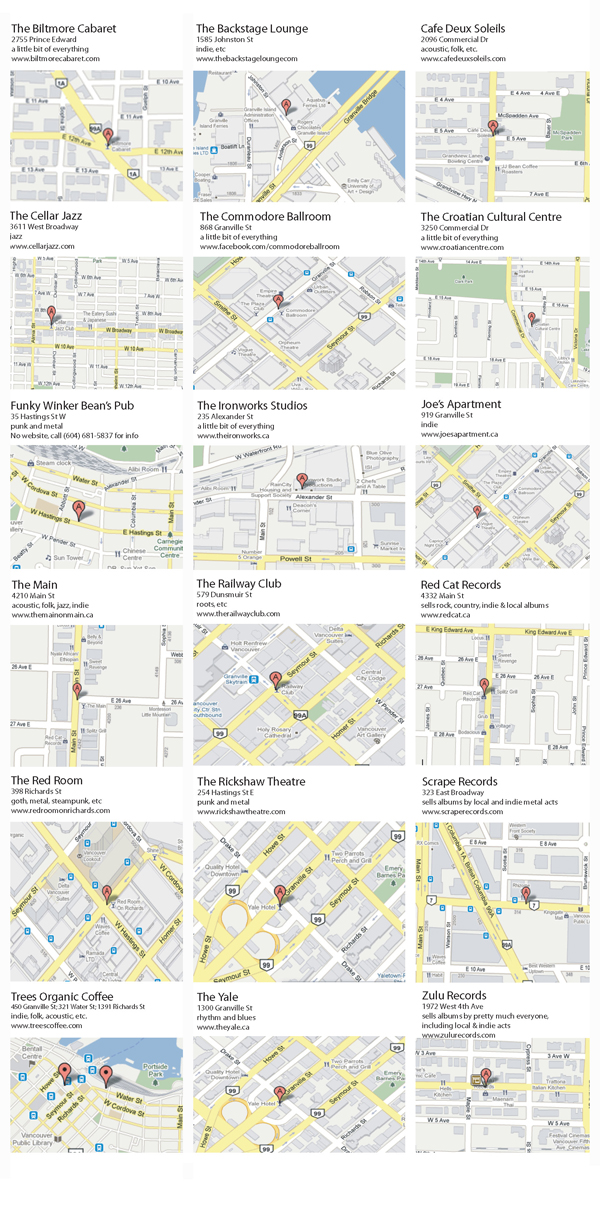

Where to find indie music in Vancouver (article below graphic):

Infographic by Amanda Punshon

We’ve heard about indie music, indie films, and other indie arts.

But what exactly does it mean?

It’s more than guys in tight jeans who listen to bands that no one has ever heard of.

Oswaldo Perez Cabrera is involved with the promotion and public relations for VanMusic.ca, a Vancouver-based website dedicated to giving exposure to indie bands.

He defines indie as being “all forms of art or culture that are outside of the mainstream media.”

Kwantlen students at the Richmond campus were also asked how they would describe indie, specifically indie music.

“Hmmm, that’s a good question,” said Alexandra Pastega, an English and marketing student. “Slightly acoustic. It has a kind of soft punk vibe to it in my opinion. Indie bands to me would constitute a band maybe like Metric. Kind of edgy but soft.”

Ian Nobak, a general studies student, said that indie means “independent. It would be maybe students making music, like downloading software and mixing it themselves.”

There is quite a difference, however, between a band such as Metric, which gets played on the radio, tours worldwide and has a large fan base, and students mixing music in their basement.

“There are people that start as indie and they move into more established companies,” Cabrera said. “There are other bands that prefer to keep it indie. Even some indie record companies, some indie labels, that start with a couple of bands, with their friends, and they become bigger and bigger. So then we have this question of how big they have to be to still be considered indie?”

It’s a question with no definitive answer. Everyone seems to have his or her own opinion.

But small or big, Cabrera believes that having independent artists is an important aspect to any city.

“Since [indie artists] don’t have any censorship or they aren’t subjected to what big companies are going to decide for them, it’s a very important voice to the culture of any city. It shows a little bit what the problems are in the city, it talks a bit about social issues, a lot of the time about environmental issues, they talk about what is happening in the subcultures of the city.”

He also believes that indie music is a form of resistance.

“It’s a resistance against the whole establishment. Because right now, most of radio and television, they tell you what to listen to, they tell you what to buy, they tell you how to think. And all these indie artists, it’s a resistance to all of that. Because they are talking about different things. They are talking about things that are contrary to what the establishment or what the mainstream is telling you to do. That’s a form of resistance.”

This is hardcore: Vancouver’s highly politicized DIY music scene through a founder’s eyes

January 17, 2011 by Amanda Punshon · Leave a Comment

Vancouver's DOA, founding fathers of hardcore. (Photo by Diane Foy, courtesy of Sudden Death Records)

By Amanda Punshon and Meagan Gill

Hardcore music is “a bunch of people screaming their heads off, playing fast. Screaming their heads off, playing fast and playing loud,” according to Joe (“Joey Shithead”) Keithley, founding member of legendary Vancouver hardcore band DOA. Hardcore has been one of Vancouver’s most vibrant music scenes for 33 years, and DOA has been there in one form or another for all of them. In fact, the band’s second album, Hardcore ’81, which was released in April 1981, is responsible for the use of the term “hardcore” as a description of their type of punk music.

Despite being an offshoot of punk, hardcore was influenced as much by folk and metal as punk itself. Keithley counts Iggy Pop, Lead Belly, Arlo Guthrie, Jimmy Hendrix and Black Sabbath as some of the musicians that most affected DOA’s music.

Perhaps the biggest, most important reason for the spread of hardcore was the conservatism of the ‘70s and ‘80s. Politicians such as Ronald Reagan in the States, Margaret Thatcher in England, Helmut Kohl in Germany and Brian Mulroney here in Canada formed “a quartet of idiots,” in Keithley’s words, that people reacted to strongly.

The political climate may be different now, but British Columbians still take social activism seriously, which, Keithley says, is one of the reasons that Vancouver’s hardcore scene continues to thrive.

“Let’s put it this way, if you’re not politically aware, you’re probably not really a punk band,” he says. “Some of the bands are into it, and they’ll play at rallies and protests and stuff like that. Not all of them…but I mean, it’s a part of activism within the punk rock scene.”

In addition to its politics, Vancouver is known for its arts scene.

“Vancouver is a happening place, arts-wise. It’s not surprising that you’d get kids who want to do something in music, they’d move out here. They probably don’t realize how tough it is or how expensive it is but they get out here and somehow they keep working on it,” Keithley says.

And it is tough. According to Keithley, it’s incredibly hard to get a record deal because major record labels no longer have the money or the sense of adventure that they did in the 1960s and ‘70s. They’re much less likely to take a risk on a band that’s not a sure thing.

In addition to that, big record store chains are increasingly less willing to stock albums by little-known bands, Keithley says. So many hardcore bands — DOA included — start their own record labels. Others turn to the Internet to distribute their material, which, for Keithley, is a mixed blessing.

“It’s hard to be heard, or what I say, get above the ‘noise floor.’ It’s kind of hard to get noticed because the most outrageous things have been done, the most screaming’s been done,” he says. But at the same time, “it’s good, the access is there, you can make an album a lot cheaper [than in the past.]”

When DOA was starting out, hardcore bands would play alongside new wave, reggae and pop punk bands. They had to in order to fill a room. But today, Vancouver hardcore has enough of a following that the lineups for most shows are filled by other hardcore bands.

Keithley is not sure what the future has in store for hardcore music in Vancouver. “It’ll just keep growing and morphing like it always does,” he says. “There’s always going to be a new bunch of kids coming along that make their own scene. I can’t predict that.”

But one thing is certain – “people are so passionate about [Vancouver hardcore],” Keithley says. “There’s a lot of support for it…there’s love there for it, and [at the same time] the support’s not there because there’s not a lot of money. It’s coming from the heart, and that’s a good thing.”

For more Chronicle coverage of independent arts in Vancouver, click here.